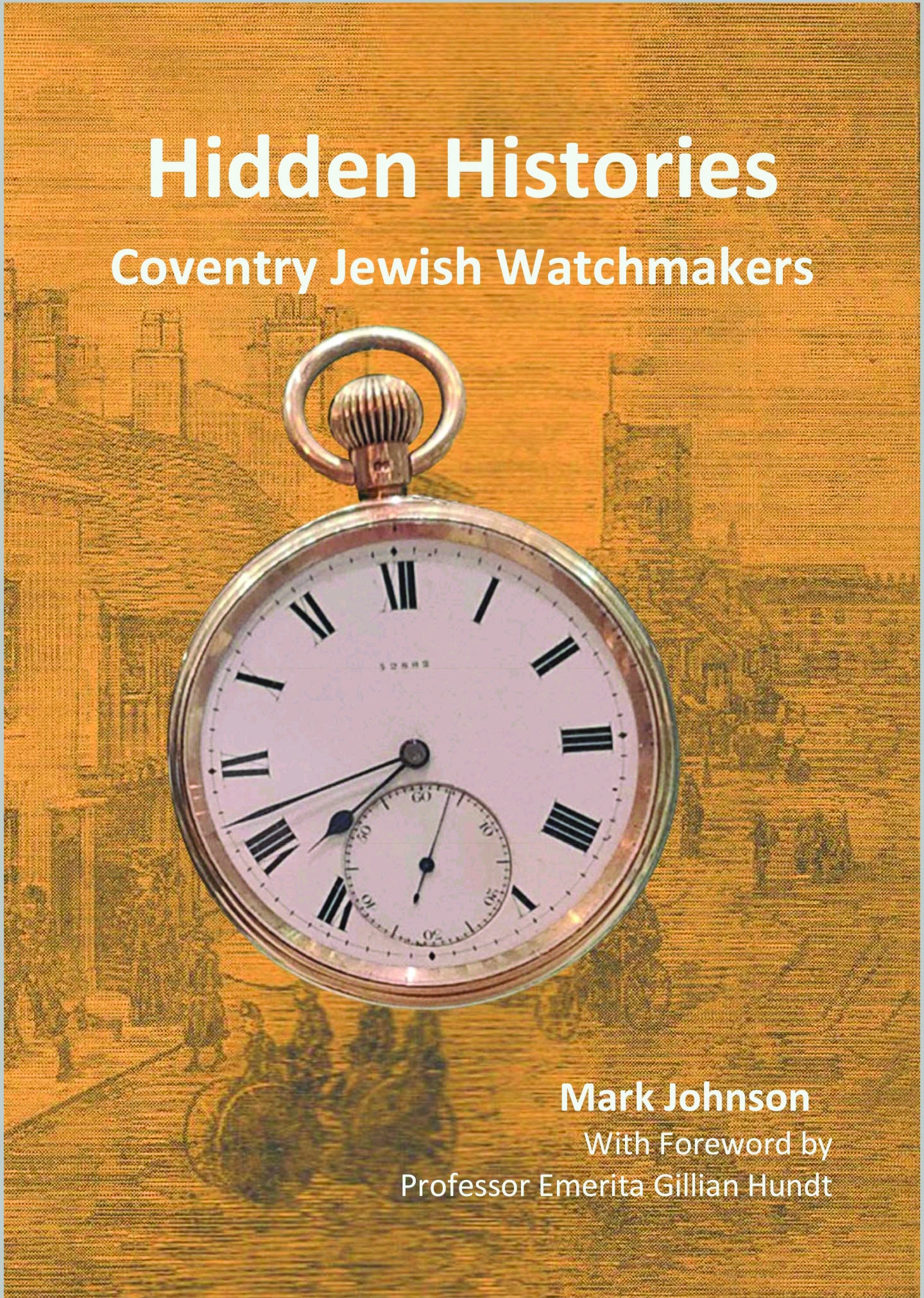

Hidden Histories

Coventry Jewish Watchmakers

by Mark Johnson

With foreword by Professor Emerita Gillian Hundt

ISBN

978-1-7393102-0-2 Softback £9.99

978-1-7393102-1-9 Hardback £16.99

978-1-7393102-2-6 eBook £6.99 or free with Kindle Unlimited

Available at: Amazon.com

This book achieves what it sets out to do and that is to review the Coventry watch industry through the eyes of the small, but significant, Jewish immigrant population of the City. It offers us a peep through the keyhole into an important part of English watchmaking history which has not yet been fully recorded.

The Coventry watch industry blossomed in the late 1700s and attracted skilled watchmakers from Europe and even further afield. The good-quality watches produced made up a large part of the total English watch output, with many being exported. Manufacturing these watches was highly labour intensive, requiring a skilled workforce at every step of production, which, in turn, made the watches an expensive product which only the well-off could afford. This left the market for those requiring reliable, but above all else, affordable, timekeepers, wide open.

English makers, including those in Coventry, were reluctant to change, which enabled the market for cheaper watches to be exploited by American and Swiss manufacturers, who gradually moved upmarket and eventually achieved the dominance in the watch industry that the Swiss still have today. This crushed the market for the good quality English pocket watch which for a time had led the world and the Coventry watch industry came to an end.

Coventry has only recently started to be credited with its important place in English watchmaking, and the eminent position achieved by its chronometers in the Kew Observatory Watch Trials, where watches using the Guild founder, Bahne Bonniksen’s, karrusel escapement consistently beat the Swiss tourbillon watches.

In this book, we learn that Alfred Fridlander submitted watches to Kew and received awards for karrusel watches obviously using Bonniksen’s movements.

Also in the book is reference to a rare commodity, a lady watchmaker – Jane Joel – who like the three or four other lady watchmakers and clockmakers of whom I am aware, carried on their husbands’ businesses after they had died.

It is interesting to see that the Coventry Jewish watchmakers mentioned in the book tended to regard the trade as a ‘family trade’ where father’s trained their son’s and passed on what was a profitable business within the family for many generations. This also happened with clockmakers. It did have the effect though that their product tended to evolve very little through the generations leaving the more go-ahead American, Swiss and German manufacturers to take advantage of ‘modern trends’.

Also in the 60 pages of this small book, we meet ‘Fair Rosamunde’, the stage name of the daughter of watchmaker Isaac and his wife Judy Cohen, who performed in Loew’s Dancing Show at Coventry’s Great Fair which was held in June each year.

In 1832, ‘Fair Rosamunde’ played the part of Britannia in the celebration of the Reform Act which gave the vote to small landowners, tenant farmers and importantly for the Coventry watch industry, shopkeepers. Isaac and Judy had been married for 78 years, when Judy died at the age of 101 in 1833. Isaac later died at the age of 107, an exceedingly venerable age for the 1830s. Perhaps we should suggest to those coming into the trade that one of the advantages of joining our trade is the fact that many watch and clockmakers, then and now, enjoy a long and happy working life!

Amongst the families taking part in the Coventry watch industry were families from Prussia, Bavaria and other parts of what is now Germany, also Poland and even Phillip Solomon’s family from Jamaica.

We hear how in 1841 following the murder of Emma Evans, who was killed in her shop in Oswestry, Shropshire, during a robbery, Moss Fridlander, a watchmaker and silversmith in Coventry, helped the Police to catch the culprit, who tried to sell the goods stolen in the crime. The Police were present when John Williams, the murderer, came to collect his money. He was arrested and in March 1842 found guilty and sentenced to death. His accomplice, Joseph Slawson, was convicted of the robbery and deported to Tasmania for seven years. He never returned!

This book will find a place in the library of anyone interested in English watchmaking for the light it shines on the watchmaking district of Coventry.

And to my friends who keep hinting at a book on Clerkenwell – ‘come on guys before it is too late!’

Chris Papworth