A hidden treasure in the Swiss Jura mountains

Maximin Chapuis, a French watchmaker and WOSTEP watchmaking instructor visits

Le Musée de la Boite de Montre – The Watch Case Museum

Housed in an old workshop that has been completely renovated, the fascinating Musée de la Boite de Montre, in Le Noirmont, Switzerland, presents visitors with two workshops that are typical of the region: a cabinet of ‘round edge turners’ from the 1850s, and a mechanised workshop from the 1920s.

It houses hundreds of beautifully preserved objects and documents that help visitors understand how watch case manufacturing techniques (rolling, stamping, turning, finishing, welding, polishing) were developed – a first in the history of watchmaking! Visitors will discover the technological and aesthetic demands of this singular profession, located at the crossroads of art and high precision. It also gives an insight into the importance of the trade to the socio-economic development of the region.

- A hidden museum in the Swiss Franche Montagnes region

This high plateau in the Swiss Jura is famous for its pastures dotted with centuries-old fir trees and home to a famous breed of leisure horse. A paradise for nature lovers, the Franches-Montagnes also has another curiosity: it is one of the world’s centres for the manufacture of watch cases, known here as ‘boîtes de montres’.

During the long winters in rather hostile environment, the locals used to supplement their agro-pastoral activities with manual labour (woodturning, lacemaking, and small-scale steelmaking). From the 1700s onwards, under the influence of watchmakers from Geneva and then Neuchâtel, they were called upon to make clock cabinets and watch cases.

- Three centuries of history

During the 18th century, the manufacture of watch cases became widespread. The work was carried out mainly during the winter, in small domestic workshops with two or three craftsmen working by hand, using spinning wheels to drive their modest tools.

However, it was in the 19th century that this occupation began to take hold, gradually relegating farming to the status of a secondary activity. After 1890, larger and larger workshops were built, now benefiting from light and electricity.

At the dawn of the 20th century, there were more gold, silver and base metal case assemblers in Le Noirmont (population 1,900 at the time) than in La Chaux-de-Fonds, which had a population of 23,000 at the time. One of the thirteen Federal Precious Metals Control Offices was opened in Le Noirmont in January 1884.

After a turbulent period punctuated by two world wars and major economic crises (1914-1945), the watchmaking industry enjoyed a veritable golden age, which ran out of steam shortly after 1970 following an oil crisis and the appearance of the first quartz movements.

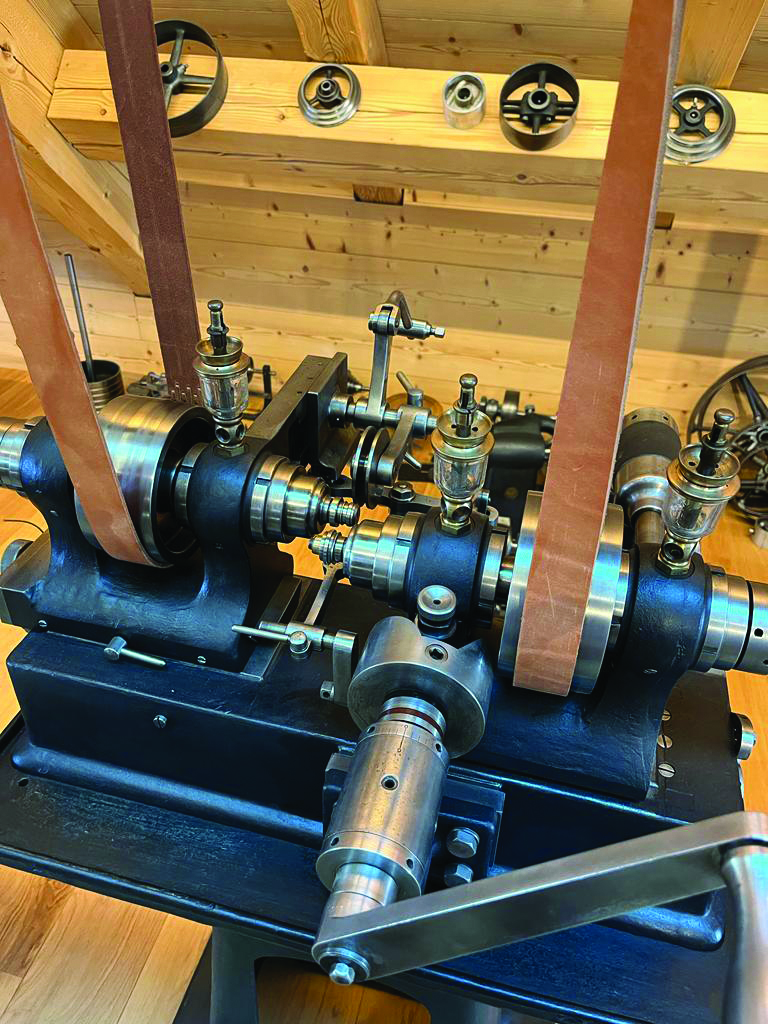

- A high-tech manufacturing workshop

It goes without saying that in those days, most machines were built with durability and robustness in mind. Safety is something to think about when compared with today’s measures. However, when you are aware of the high quality objects made in this type of workshop, they are a marvellous illustration of the talent possessed by these genius craftsmen.

What is most impressive when you enter this awe-inspiring room is the intimidating set of sewn leather belts that move around very long shafts fixed to the ceiling, which are themselves driven by belts, see Figure 1, 2 and 3.

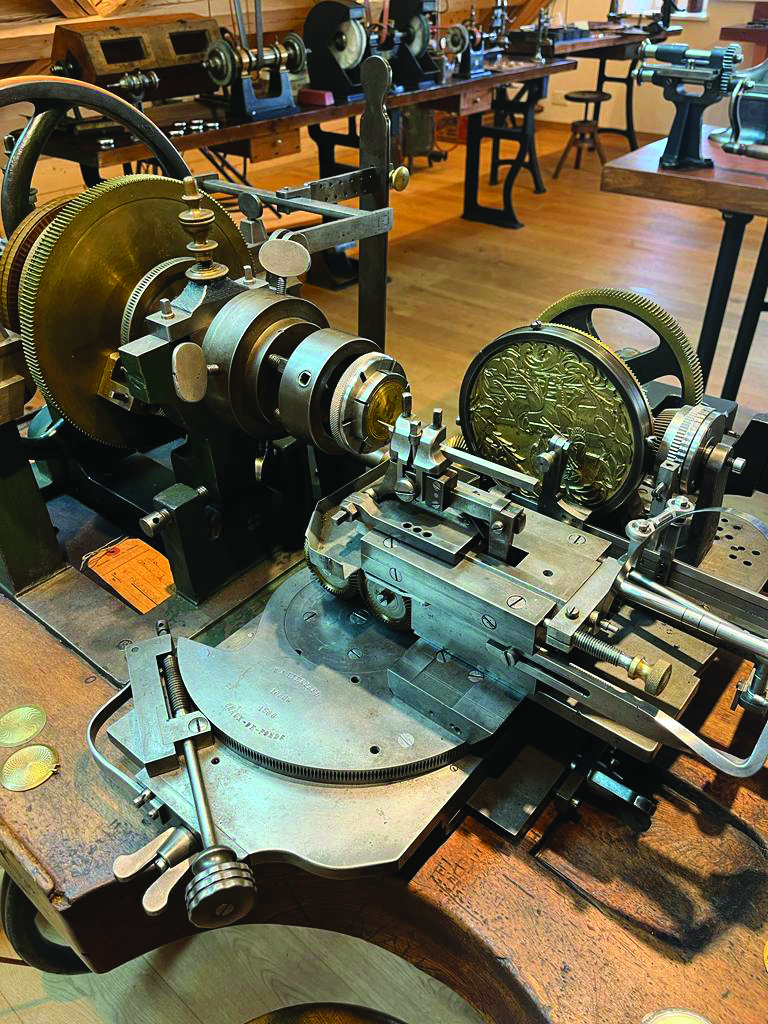

You will see Guilloché machines with integrated pantographs for copying motifs already engraved by hand, Figure 4, as well as a machine used to produce decorations with motif rollers mounted on a head rotating around the box, Figure 5. At the end of the largest room, large cast-iron presses sit majestically, Figure 6. They were used to stamp blanks or simply to shape square or round bars to form the centre of a pocket watch case.

Under the windows, a line of metal lathes with spindles prepared for mass production and a marvellous automatic machine for sharpening chisels on a lapidary, Figure 7. These lathes are to be compared with the treadle lathes at the back of the workshop, which are used more for small precision work, Figure 8. They were positioned under the north-facing windows to get as much light as possible without ever having to face direct sunlight and so avoid being dazzled. In this picture you can also see special paraffin lamps in gilded bronze with a long glass tube which were present in classic ancient workshops.

Next to these machines, there is an impressive machinist lathe, Figure 9, with all its attachments and devices. Even with its weight and robustness, it was powered with a massive treadle

underneath meaning the machinist had to work with both hands and feet to regulate the speed. Figure 10 gives an idea about the type of forge employed to carry out heat treatments on newly made steel parts.

If you would like to visit the museum (which is only open on demand) you can find out more on their website:

museedelaboitedemontre.ch