Calibre Jones watches were the first watches made by the International Watch Company (IWC) and are now around 150 years old, Figure 1.

These early models were designed and produced by IWC founder, Florentine Ariosto Jones, a young American who crossed the Atlantic Ocean to Schaffhausen in 1868. Unusually this medieval city is located in Switzerland’s north east, far away from the Jura valley where the main watch industry has been located for many years.

Jones introduced the ‘American system of watchmaking’ to Switzerland. This mechanisation of watch manufacturing had already been taking place in North America since the 1850s, with large American factories such as Waltham and Elgin producing tens of thousands of watches each year.

The style of watch production in Europe at this time was still a very traditional craft, completely carried out by hand.

After the introduction of machines, imported from the US, IWC produced around 26,500 watch movements between 1872 and 1878. When Jones left Schaffhausen in 1876, about half of the production had been completed and exported to the USA.

Part of the concept was that Jones did not case the movements in Schaffhausen. This was done in the US because it was considered to be more cost effective. The highest quality movements received a 14 or 18 carat gold case, the others a case made of coin silver. The typical US customer would buy a watch movement in a jewellery shop where a case to his taste could be selected and mounted.

The successor to Jones, Frederic Ferdinand Seeland inherited unfinished Jones movements. Among them were all the open face (lépine) movements of which none had been sold during the Jones period. The lépines were predominantly cased in European countries but not in the IWC factory.

To find a complete original Jones cased watch is a rarity for several reasons. Over the many decades gold cases have been removed for their scrap value. It is estimated that less than five percent of all Jones watches have survived. Only 400 watches are known to exist, representing two percent of all watches made. In Europe compared to the US, two World Wars have resulted in fewer examples remaining, Occasionally Jones movements are offered on auction sites, often without case, dial or hands and in a very poor condition.

The unrestored IWC Jones movement, pattern C.

Restoring such a watch can be a real challenge. Nevertheless, there are collectors, interested in the early history of IWC, who are happy to embark on such a task, sometimes not realising where it will end.

The first part of the challenge is to find a competent watchmaker. In many European countries the profession of watchmaker changed completely after World War II. Most watchmaking schools have disappeared and there are few training programmes. The education of a ‘watchmaker’ is predominantly limited to servicing and replacing of worn parts.

Apprenticeships are offered by jewellers or watch importers, however, the basic skills of working on a lathe to make a wheel, pinion or lever are only mastered by a very few, primarily because there is limited demand. The basic skills are not considered to be cost effective if cleaning, lubrication and mounting of a spare part does not bring the final solution.

Swiss watch factories decline the restoration of their own older models as spare parts are no longer available. Of course they employ excellent watchmakers but they are busy building new, exclusive complicated timepieces and do not perform restoration. Only a few high end brands make an exception for vintage watches of significant value.

This evolution means that the original trade of watchmaking has faded away. However, for hard core collectors and purists it is a relief that the craft of watchmaking has been preserved in Britain and Ireland.

It is a pleasure to note that there are several horological training facilities in the UK helping to ensure young craftsmen and women of the future.

Here I want to show you how ‘a piece of junk’ can be changed into a beautiful pocket watch in working order. The watchmaker who performed the restoration is a Fellow of the British Horological Institute, who wishes to remain anonymous because he is overloaded with work, has a long waiting list and does not want to disappoint customers, mainly from abroad.

Making the barrel for the main spring. |  The new wheel. |  Newly-made ring for better movement fit. |

Assembled cleaned and restored movement. |  The restored movement mounted. |  Restored watch, dial side. |

The movement shown is what remains from a key-wind, key-set, pattern C, calibre Jones pocket watch, Figure 2. The pattern C is one of seven different patterns of Jones movements that correspond with different qualities. It has 11 jewels while the other patterns have 14, 16, and, in one pattern, even 20 jewels. Because it belongs to the lowest quality virtually all pattern C examples have disappeared.

Once broken, repair was not considered worthwhile by watchmakers as calibre Jones watches were not collector items. Only five of these watches have been documented so far so, because of its rarity and history, it was decided to restore this movement.

The diagnosis after disassembling was daunting. There was no case, a rupture in the mainspring barrel, several wheels were bent or worn, the balance staff was broken, the dial cracked and there were no hands.

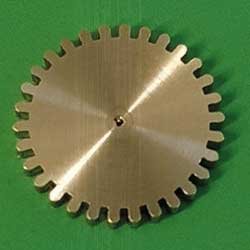

Not surprisingly, a donor movement for spare parts was not available. A new barrel had to be made, along with the necessary cutter, Figure 3. The hour and minute wheel had to be manufactured, Figure 4. The hair spring needed to be repaired and a new balance staff had to be made. The enamel dial could not be repaired either, but luckily an identical original dial was found, as Jones used the same type of dial on the more common B pattern models too. A full set of original Bréguet hands was also available .

It was impossible to find an original case because so few of these watches now exist. As it was far too expensive to make a complete new case for an 11 jewel watch of modest quality, it was decided to use an American hunter case, as the movement is hunter orientated.

A suitable case would appropriately be from the same era, i.e. 1860-1880, however, the cases for IWC calibre Jones watches generate several problems. The American cases were already engine turned at that time and they had standardised sizes. The movements from Schaffhausen had a diameter of 43.3 or 43.7mm, which is different to the standard sizes for American movements.

An American 16 size case has a diameter of 1,700 inch (43.18mm) making it too small for a Jones movement. American size 18, measures 1,767 inch (44.87mm) so is too wide. A size 18 case can be used but then a clearly visible gap is present between the inner diameter of the case and the outer diameter of the movement, resulting in a poor fit. We chose this option and to fill the gap, a ring was made, providing an acceptable functional and aesthetic result, Figure 5.

The selected hunter case must have an intact lid in order to drill two holes where the key for winding and setting can meet the pinions. It is very unlikely that the hole for winding would be in the correct place in an existing case. In addition, a hunter case with an in-tact cover lid has a winding crown and for the functioning of a key-wind, key-set Jones, a pusher is needed to replace it. All steps during the process worked out satisfactorily.

Figure 6 shows the movement after it has been meticulously cleaned by hand.

Once the full restoration had been completed, the watchmaker returned the timepiece to the collector who was delighted, describing the transformation as ‘magnificent’, Figure 7. The dial also fulfilled all expectations, Figure 8.

It can be concluded that restoration of a 150 years old timepiece is quite an adventure. The key factor for the collector is to find the right, competent craftsman.

For pure economic reasons few owners will embark on such time consuming and labour intensive enterprise. However, a collector or a customer with a special and dear family piece might decide upon such action and the end result will provide great satisfaction for both the restorer and the owner. Together they have saved a rare piece of watch history.

Acknowledgement:

The author wants to thank Professor Alan Myers for reading and improving the manuscript.

References:

D.Seyffer, T. König and A. Myers., F.A. Jones-His Life, Legacy and Watches Ebner Verlag GmbH & Co.KG, 2011, Ulm and IWC Schaffhausen.

A. v.d. Meijden, J. Blonk, The IWC Calibre Jones. History and Restoration of a Rare Pocket Watch, HJ February 2019, Vol.161, No 2, p72-76.