BWCMG member Colin Andrews has embarked on a very special project – hand-making British watches using parts of an old war-time spitfire.

Since embarking upon my career as a watchmaker I always had the ambition to be just that – a maker of watches. I was fortunate that when I initially contacted my local horologist for advice on how best to train, that happened to be Robert Loomes, who was, and continues to be, incredibly enthusiastic and supportive.

After enrolling as a full-time horology student, I learned about the historic role Britain had played in the development of watchmaking and the subsequent decline and collapse of the industry. It seemed a shame, but I could see other nations – notably Germany – had enjoyed a tremendous revival of their watchmaking industry around Glashütte and in my optimism I didn’t see any reason why the same couldn’t apply in Britain.

As the Second World War raged in Europe, the world’s most famous aircraft – the Spitfire – was at the forefront of operations to liberate the continent.

Soon after D-Day on 30 July 1944, one of these Spitfires, registered as ML295, was being flown by pilot Harold Kramer over Nazi-occupied France. It was on its 67th mission.

The aircraft was an LF Mark 9, which was a Spitfire variant designed for low altitude flight. At the time it was the cutting edge of Allied aircraft technology, powered by a 27 litre V12 Rolls Royce Merlin 66 engine, producing 1,705 horsepower and capable of reaching over 400mph. It was armed with two machine guns and two cannons in its wings and enough ammunition for 12 seconds of sustained fire.

This formidable combination made the Spitfire both fast and deadly, and earned it a reputation, among both Allied and German pilots, as the greatest fighter aircraft of the war.

Spitfire ML295 had made a successful attack on a German convoy, when his squadron heard Kramer exclaim over the radio that he’d been hit by enemy anti-aircraft fire and his engine had stopped. They watched as Spitfire ML295’s propellor spun to a stop and the aircraft silently glided out of formation and out of sight.

Despite having only seconds to make his unplanned landing, Kramer skilfully managed to bring the Spitfire down in a marshy field. He emerged from the aircraft unharmed and made a dramatic escape. Now behind enemy lines, Kramer managed to evade capture for a month, before making his way back to Allied lines and his relieved squadron mates.

So, I founded my own business, Great British Watch Company, with the aim of eventually producing my own British-made watches.

Over the next seven years I produced my first watch and built my website, which featured content about aspects of watchmaking and had a particular focus on British watchmaking. It has proven to be popular and since its creation has attracted more than five million unique visitors.

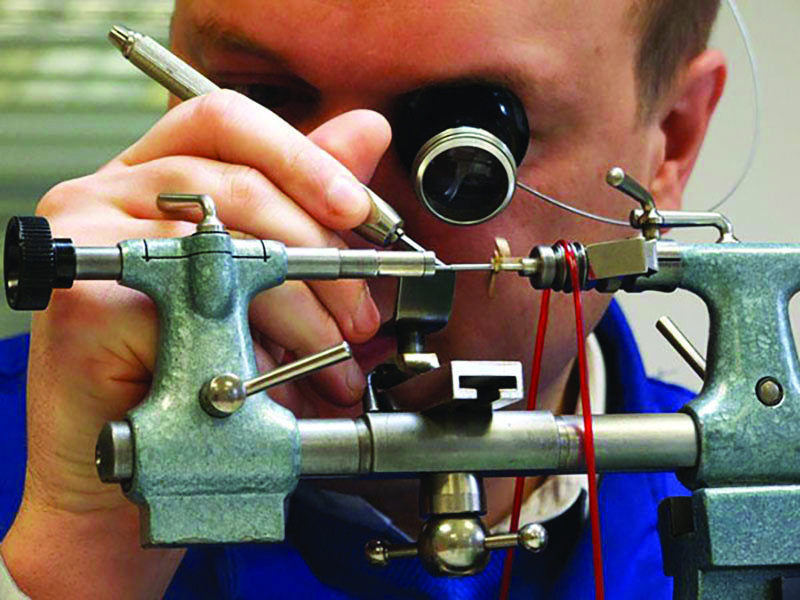

The work on my watch began while I was still studying for my BHI exams and it continued during the evenings and weekends when I began to work full-time in the industry.

Although that watch is finished, there are always parts that I would want to remake or redesign. One of the reasons it had taken so long to complete was that as I finished a new part and my skill level increased, I would look at some of the earlier work and think that I could remake that a bit better. This would start a domino effect and eventually I’d find myself remaking other older parts. That cycle happened 10 times before I decided to finally accept that the watch was as finished as it would be.

Clearly, replicating such a long turnaround wasn’t something that could become a commercial enterprise and so I was always on the lookout for inspiration for a series of watches that I could make for the public.

Since its crash in 1944, Spitfire ML295 had remained where it landed; submerged in the middle of a pond in Northern France. Almost 75 years later, the wreck was recovered and transferred to Biggin Hill Airfield in Kent to undergo a full restoration.

I became linked to the Spitfire through my cousin, an experienced pilot who had just started training to fly Spitfires. The restoration of Spitfire ML295 had not yet begun and I was invited down to the hangar to take a look; even although at this stage it was still just a skeletal frame. After chatting with the owner and engineers who would work on bringing the Spitfire back to life, I was made aware that there would be parts of the original Spitfire that couldn’t be reused in the restoration – with their condition not being suitable for an airworthy aircraft – and so I had an idea that I could incorporate some of that material in a commemorative watch.

Early into the project I realised the incredibly powerful connection that people felt with the Spitfire. By creating an emotional link to the DNA of the Spitfire and her pilots, it was my intention that the watch was not just a timepiece, but also a visceral reminder of those pilots and the sacrifices they made.

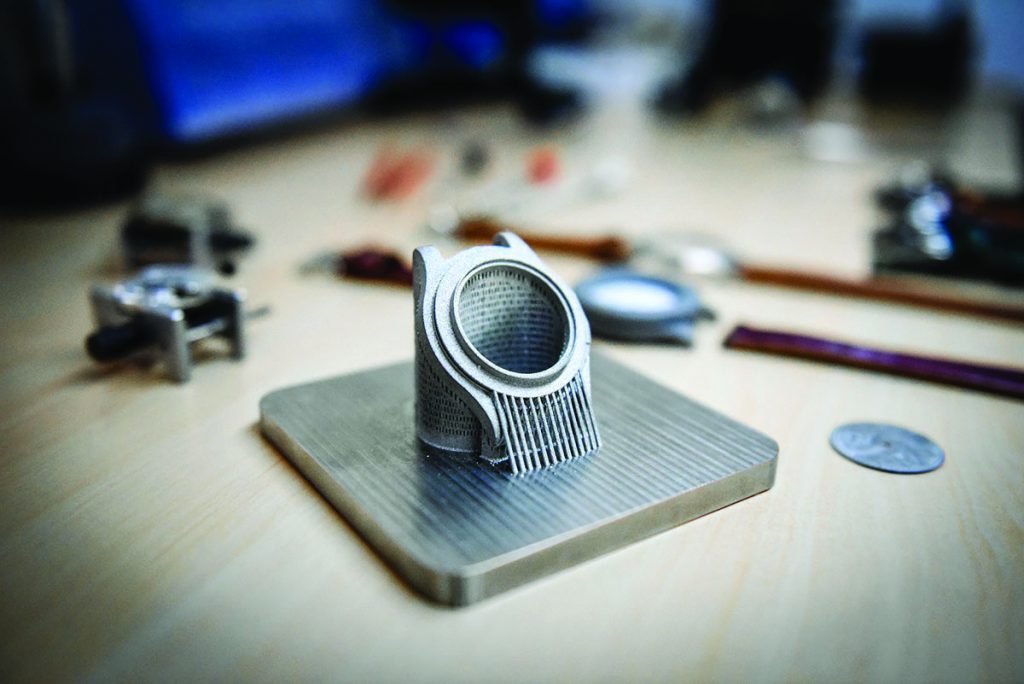

With the scale of the project becoming apparent, I knew that this wasn’t something that I could complete in my spare time – if I wanted the endeavour to be successful, it would need my full attention. So I made the decision to leave work, create my own workshop and begin working on the project full-time.

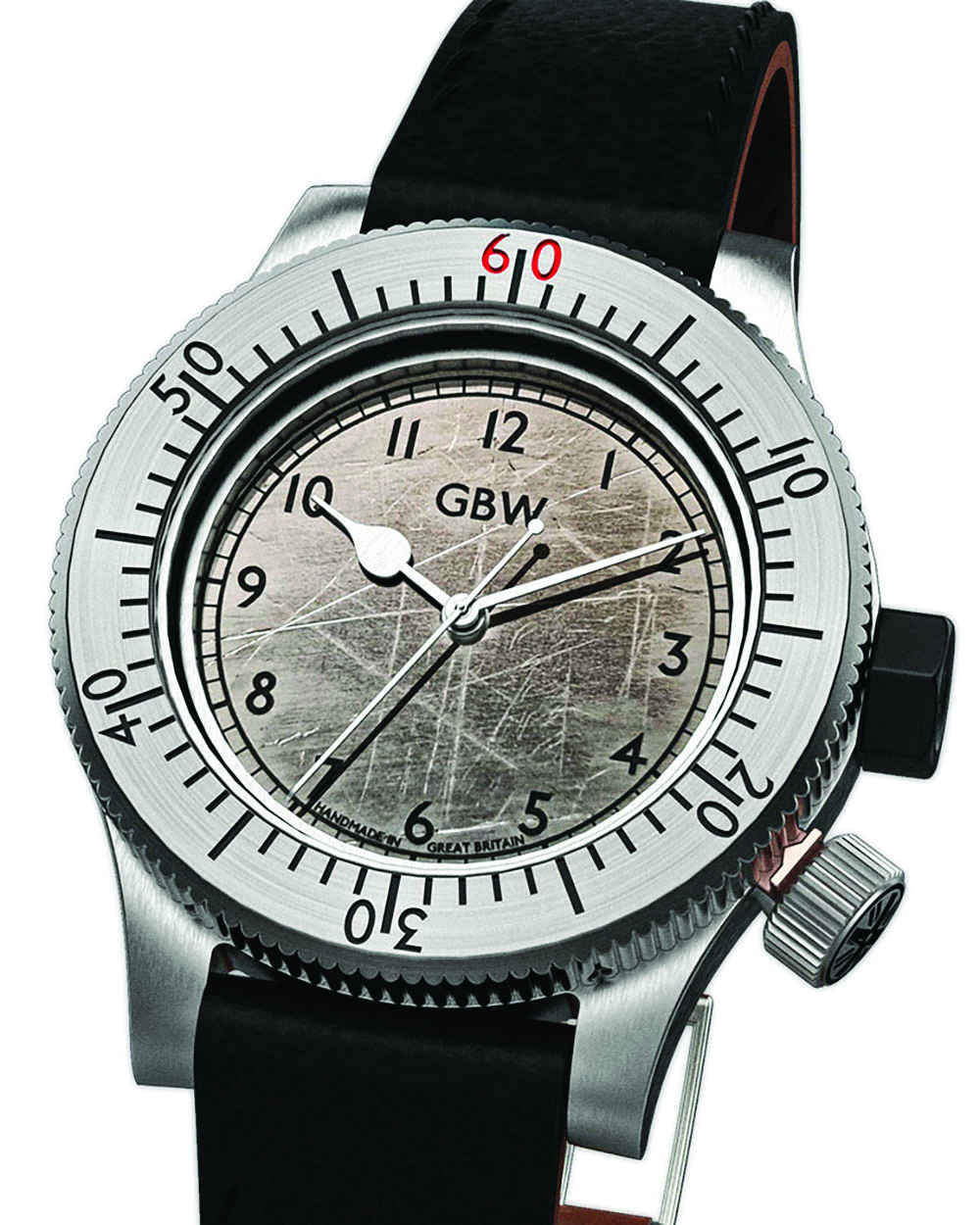

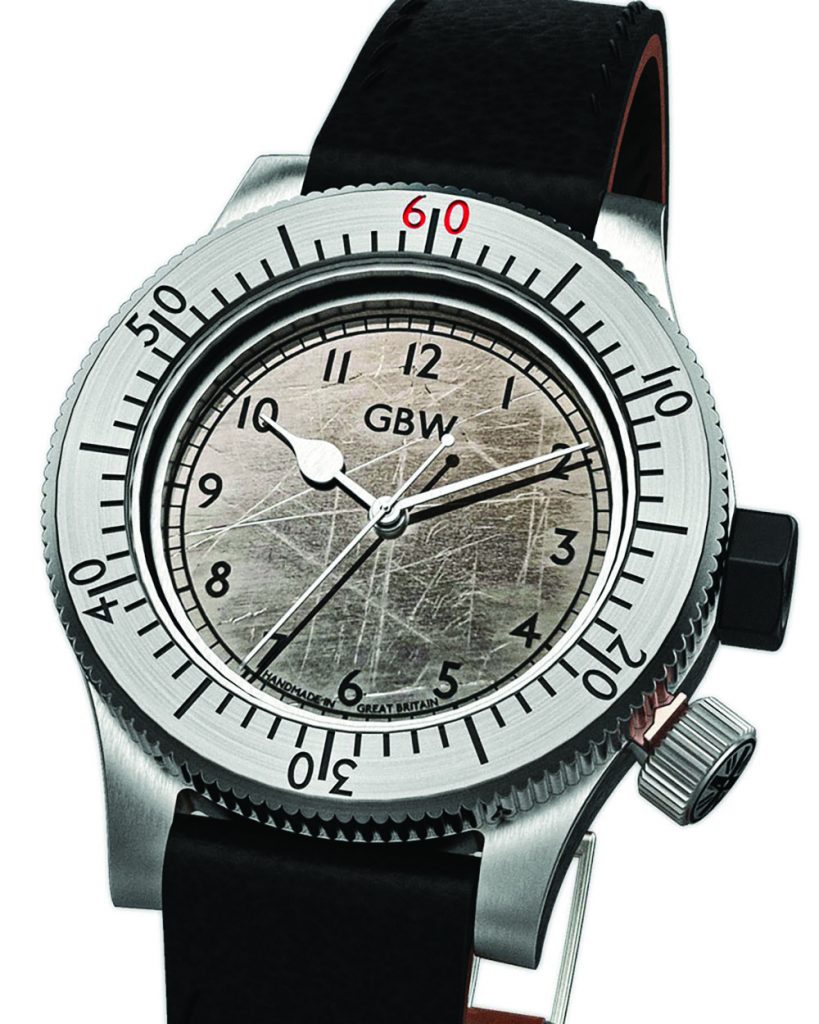

After some research into the design, I settled on an homage to the watch that many Spitfire pilots wore, the Omega CK 2129, also known as the Weems watch. Working alongside current Spitfire pilots to help design the timepiece, we came to modify and upgrade the original watch design so that they could wear it today as part of their pilot’s uniform.

I also aspired to build the watch entirely in Britain – that was my company’s objective, after all. To be able to complete such a series of watches though, I would need help, as I did not have access to the sort of high precision automated machinery that would be needed, nor the time to create each component of the watch by hand, as I had done with my first watch.

This was certainly a challenge, as the UK currently has a very small watchmaking industry and there was not an opportunity to use third parties to readily produce parts needed – as would be possible if I went to Switzerland or China.

Despite this lack of infrastructure, the difficulty of working with material from the 1940s and the onset of a global pandemic I knew, having already made my own watch by hand, that it was achievable.

There was certainly world-class skill, expertise and equipment in the UK – it was all just working within different industries. So, my initial challenge was to try to convince this talent to become involved with the project. I was aided in this task by being able to draw upon the powerful name of an iconic aircraft.

Even after more than 80 years since the Battle of Britain, when people hear ‘Spitfire’ the hairs stand up on the back of their neck and they are reminded of the deadly ballet these men and their machines performed, as they fought for the salvation and liberation of those enslaved by tyranny.

With persistent enthusiasm, I found world-class artisans and engineers who were eager to be part of the project – the majority being within just 20 miles of my workshop. With their help, the watch turned from an idea into a reality.

The watch initially had the working title of ‘Spitfire Watch’, although it soon became known as ‘The Few’, in honour of the name given by Winston Churchill to those few pilots who saved Britain during her darkest and finest hour. It also represented the few remaining Spitfires that are left and the limited number of watches that would be created to celebrate the heroic pilots and their iconic aircraft. As my research uncovered the story of the Spitfire from which The Few would be made and the men who flew her, it became apparent that to do justice to their legacy I needed to build that soul into the watch.

Work soon began to get underway on the watch and progress was being made – then Covid19 arrived. This frustrated a lot of the development, however it allowed me to concentrate on other areas – particularly the research into the Spitfire and the pilots.

To be continued…